Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common clinical problem frequently requiring hospitalization. It can vary in degrees, from massive life-threatening hemorrhage to a slow, insidious chronic blood loss. The overall mortality for severe GI bleeding is approximately 8 percent, but this number is diminishing with the arrival of superior diagnostic techniques and newer medical treatments. Many bleeding episodes resolve on their own, but it is still imperative that the bleeding site be determined. An exact diagnosis may prevent a recurrence of bleeding and may help us treat future episodes more effectively. Also, making an accurate diagnosis can allow a patient to be treated appropriately for the underlying condition that caused the bleeding in the first place.

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of GI bleeding depend on the acuteness and on the source of the blood loss.

Mild, chronic GI blood loss may not show any active bleeding, but can still result in an iron deficiency anemia. Many of these patients never notice any blood loss, but it occurs in small amounts with the bowel movement so that it is not noticeable. Blood in the stool often can be detected by hemoccult testing (testing for blood in your stool) during a routine office examination.

In more severe cases of chronic or acute bleeding, symptoms may include signs of anemia, such as weakness, pallor, dizziness, shortness of breath or angina. More obvious bleeding may present with hematemesis (bloody vomit), which may either be red or dark and coffee-like in appearance.

Blood in the stool could either be bright red, burgundy and clotted, or black and tarry in appearance, depending on the location of the bleeding source. A black, tarry stool (melena) often indicates an upper GI source of bleeding although it could originate from the small intestine or right colon. Other causes of a black stool might include iron or ingestion of bismuth (Pepto-Bismol). Hematochezia, or bright red blood can be mixed in with the stool or after the bowel movement and usually signifies a bleeding source close to the rectal opening. This is frequently due to hemorrhoids; however, you should never assume rectal bleeding is due to hemorrhoids. Conditions like rectal cancer, polyps, ulcerations, proctitis or infections can also cause this type of bright red blood.

How is it diagnosed?

If it is suspected that the bleeding is in the upper gastrointestinal tract, then an upper GI endoscopy is usually the first step. This is a flexible video endoscope that is passed through the mouth and into the stomach while the patient is sedated. It allows the doctor to examine the esophagus, stomach and duodenum for any potential bleeding sites. If a site is detected, therapeutic measures can be used to control the bleeding. For example, a bleeding ulcer may be controlled with use of cautery, laser photo therapy, injection therapy or tamponade.

If the bleeding is suspected to be in the lower GI tract or colon, then a colonoscopy is usually performed. In a colonoscopy, a video colonoscope is passed through the rectum and across the entire colon, while the patient is sedated.

Other diagnostic methods for detecting a bleeding source might include a nuclear bleeding scan, angiography, or barium GI studies.

In the case of chronic low-grade or occult bleeding which may result in anemia, the work-up to discover the source of the bleeding is usually done on an outpatient basis. Generally this consists of a colonoscopy and/or upper endoscopy to look for any potential sources of chronic blood loss.

Once the cause for the blood loss is determined, appropriate treatment and management recommendations can be made.

How is GI bleeding treated?

If GI bleeding is very active or severe in nature, it may require hospitalization. Shock can occur when blood loss approaches approximately 40 percent of blood volume. If there is evidence of hypotension (low blood pressure) or a fast heart rate, dizziness, or light-headedness, then treatment would include IV fluids and monitoring of the blood count, with blood transfusions given, if necessary.

While in the hospital, the patient will continue to be monitored closely and certain medications will be employed in an attempt to stop the bleeding. In addition, diagnostic tests are performed.

In some cases, GI bleeding will stop spontaneously.

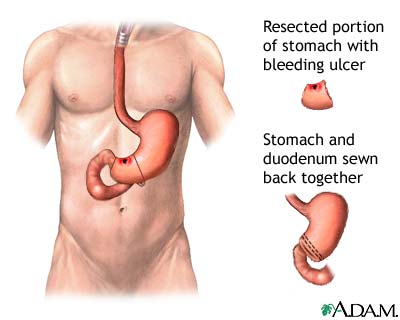

If the bleeding persists, despite all of the above-mentioned therapeutic techniques, then surgery might be required as a last resort.

What causes GI bleeding?

The most common cause of an upper GI bleed is an ulceration, either in the duodenum (just beyond the stomach), in the stomach lining itself, or in the esophagus. Esophageal varices, or varicose veins, are usually the result of underlying chronic liver disease like cirrhosis and these can often bleed very briskly. A tear at the junction of the esophagus and stomach sometimes also occurs as a result of repeated vomiting or retching. In addition, tumors or cancers of the esophagus or stomach can also cause bleeding.

Factors that may aggravate upper GI bleeding include use of anti-inflammatory medications (in particular aspirin other arthritis drugs), underlying chronic liver disease, thinning of the blood from certain medications like Coumadin, or underlying medical problems like chronic renal disease, cardiac or pulmonary diseases.

The most common cause of bleeding from the lower GI tract or colon is diverticulosis. This accounts for over 40 percent of these cases. If diverticular disease is not found, then a patient could have an angiodysplasia which is a tiny blood vessel lining the colon that sometimes can bleed briskly or ooze chronically. Colon cancers or colon polyps might also produce lower GI bleeding, as well as different causes for colitis. Colitis is an inflammation or ulceration of the lining of the colon that could be due to ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, radiation therapy, or poor circulation to the colon itself.

For More Information

To learn more about this topic, please visit: